![]()

Going to the mat with lua teacher Michelle Manu

Story by Beau Flemister. Photos by Adam Amengual.

“Hit me,” she says. I hesitate. “Come at me and try to hit me!” she insists. Call me old-fashioned, but I don’t want to hit a woman, let alone a grandma. But Michelle Manu, a tenth-degree black belt in the Hawaiian martial art of lua and a Knight Commander of the Order of King Kamehameha I, is no ordinary tūtū.

I approach and throw a halfhearted right jab. She parries nimbly, pivots her hip into mine, interlocks our bodies and twists me down to the mat. Just like that I’m on my back, tūtū hovering above me with her hair pulled back in a tight ponytail, eyes fierce, one fist cocked and ready to detonate.

“See what I did there?” she asks, helping me up. I nod, trying to catch a breath. “Lua is a corkscrew motion at extremely close contact. Normally, combat is trained in a three-and-a-half-foot-wide circle. So, you’re not throwing opponents away from you like other martial arts; it’s a crunching down of your opponent.”

Michelle Manu, a.k.a. kumu (teacher) Michelle, hasn’t broken a sweat. She’s in phenomenal shape, a toned 5’6” with square shoulders and fists like small bricks. She practically glows with intensity. While Michelle’s list of accolades is impressive —World Black Belt Martial Artist of the Month (2002), Masters Hall of Fame inductee (2006), Martial Arts History Museum Hall of Fame (2016), the first female Knight Commander of the Royal Order of Kamehameha I, given for her work perpetuating lua—martial arts isn’t even her day job. She earned a JD in 2007 and is a legal professional. If that weren’t enough, she’s currently working toward a certificate in physiology through Harvard Medical School.

The studio she rents at Shuyokan Ryu Martial Arts Center in Costa Mesa, is typical dojo chic. A wall of mirrors, a floor of springy rubber mats, a punching bag that Michelle broke a couple weeks ago while hitting it. She grabs a large Dakine travel surfboard bag from the corner, unzips it and empties out a dozen terrifying wooden weapons and a rubber stunt knife. She tosses me the knife and commands me to attack again, quickly crushing me down like a collapsed Slinky.

Michelle pops up, even more energized. “You don’t stop, do you?” I say, hoping for a quick break. “I’m just addicted to movement,” she smiles. “That’s my drug of choice for as long as I can remember.”

Raised in Southern California by a Hawaiian father and a mother from the Mainland, Michelle was a bit of a wild child, constantly seeking ways to channel that well of energy. She took tap dance, jazz dance and gymnastics but found her true love in martial arts at the age of nine in her first kempo class. Ten minutes in and she was hooked, she says. “When I was nine I wanted a Porsche, I wanted a black belt and I wanted to be president of the United States,” she laughs. Having seen her Porsche parked in front of the studio, I tell her she’s still got time for the 2020 election.

Michelle dabbled in aikido and some Korean martial arts while simultaneously dancing hula, going on to perform professionally for eleven years. She danced with the Tuia‘ana Polynesian Troupe and with the Island Dancers and Na Pua o Hawai‘i, performing across the United States in museums, art institutes and even aboard boats on Lake Michigan. But it wasn’t until she was 22 that she discovered lua—the ancient Hawaiian and brutal form of hand-to-hand combat—in a phone book, of all places.

“Wait, you danced hula while doing martial arts?” I ask, as though the grace of the former would conflict with the violence of the latter. “Absolutely,” she says. “One is contact, the other is not. Lua and hula are intimately intertwined.” She uses hula movements to illustrate lua maneuvers that a student might have trouble learning, she says, and claims that lua was preserved in hula. Both practices were banned after the arrival of Western missionaries, but as hula re-emerged, lua maneuvers were hidden in plain sight within the hula moves.

With the little time I’ve got before I’m crumpled into the mat again, I ask Michelle about how she discovered lua and became a tenth-degree black belt in the art. “Well, the belts were actually ‘Ōlohe’s idea to make lua more ‘legit’ among the wider martial arts community,” she says. “‘Ōlohe made it very clear that lua was never meant to be a sport.”

Michelle can barely speak of her ‘ōlohe (master) Solomon Kaihewalu without pausing. A mentor and master she credits with changing her life, Kaihewalu passed away at age 83 a week before I met Michelle. At age 22, Michelle discovered Kaihewalu and his Lua Hālau o Kaihewalu in the Orange County Yellow Pages while searching for a martial art that was closer to home, genealogically speaking. She remembers calling the number and getting Kaihewalu’s wife on the line. Michelle introduced herself—and was quickly hung up on. She called back, thinking it had been a mistake, and the woman snapped, “He doesn’t teach women!” Click. Not one to back down, Michelle called yet again and said she wouldn’t quit calling until she got the boss on the line. So he answered, and after a brief conversation Kaihewalu invited her to a class.

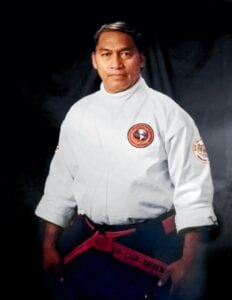

“I walk in and it smells like sweat and stale blood,” she smiles. “It smelled of … injuries.” The dozen or so men in the class mostly ignored her. Then Kaihewalu stepped into the room, and every man snapped to attention like soldiers. ‘Ōlohe was a fierce bear of a man with paw-like fists and a sensei unlike any she’d previously met. A nearly full-blooded Native Hawaiian, Kaihewalu was born in 1935 to a mother of ali‘i (royal) lineage and a father who began to train him in lua by age six. A US Air Force man through the ’50s, Kaihewalu taught pilots lua, specifically how to use their bootlaces as a ka‘ane (strangling cord) in case they were captured. Kaihewalu met his wife while in Germany, then moved to Southern California where he’d since started lua schools in the San Fernando Valley, Orange County and even in Mexico.

“‘Ōlohe was old-school,” Michelle laughs, tearing up. During that first class, she recalls him hitting a couple of the men, swearing like a sailor, barking orders half in Hawaiian, half in pidgin. After the lesson he asked her what she thought. “I thought … this is perfect. It was exactly what I was searching for. It was as if everything in my life had led me to that moment.”

Over the next two years, Kaihewalu deprogrammed Michelle of everything she’d previously learned, instilling lua into her every movement and advising her not to practice any other martial art. He hadn’t taught a woman since the early ’80s, and Michelle felt like most of the men in the class were just waiting for her to drop out. She took her lickings—a broken rib, hematomas, concussions and neck injuries—but she didn’t quit.

Michelle tells me that Kaihewalu’s methods were criticized when he brought lua into the public sphere in the 1960s, even receiving death threats from Hawaiians back home for teaching lua to Mainlanders and non-Hawaiians. He caught flak for teaching a woman, even though female warriors figured in Hawaiian oral histories going back centuries. She shows me a book that she helped Kaihewalu put together called Ancient Hawaiian Martial Art of Kaihewalu ‘Ohana Lua, a history and how-to for the Kaihewalu school of lua. Perhaps the most significant thing lua and Kaihewalu brought to Michelle’s life was a connection with her Hawaiian identity. Her father, who had left the Islands before the cultural renaissance of the 1970s, always discouraged her from celebrating her heritage. He deterred her from learning the Hawaiian language, let alone a “savage” art like lua.

“When I practice lua, I feel like I’m cleaning my bloodline for the sins of my father, who may have had a negative perception of our identity,” she says. “I feel like a conduit. The knowingness is so much deeper for me, like I’m led by something within my blood, a deeper muscle memory.… The movements are so organic.”

It took Michelle two years from that first class to prove to Kaihewalu that she belonged there. She’d go on to become the first female kumu lua (lua teacher) in modern times.

“Why don’t we practice with the weapons?” she says, walking over to the board bag and picking up the lei o manō, a wooden hand paddle edged with razor-sharp shark teeth. Then she picks up a hoe, a canoe paddle, and swings it through the air, using her whole body with an efficiency born of long practice.

Michelle says while today lua is largely aimed at dislocating joints, traditionally it was more brutal. It involved biting flesh and tearing muscle. It sought to break bones, with or without a weapon, to “bundle up” the opponent. In Kaihewalu’s tradition of lua, an opponent is disabled joint by joint and forced to the ground, putting pressure on their bodies to break their bones. At the same time, lua warriors were also master healers adept in practices like lomilomi, which developed to restore the wounded, especially on the battlefield.

Once reserved only for the ali‘i warrior caste of pre-contact Hawaiians, lua has been around for centuries, brought to the Hawaiian Islands by Tahitian voyagers. Perhaps the most notable lua practitioner was King Kamehameha I. ‘Ōlohe, the word for a lua master, literally translates to “hairless,” as ‘ōlohe lua would have all hair plucked from their bodies; then they’d be slicked with kukui nut oil and pig lard so that they would slip easily from an enemy’s grip.

With the arrival of Western missionaries in the 1820s, lua—along with hula, surfing and the Hawaiian language—was banned, deemed both too violent and too sexual, a “dark art” that encouraged idleness. Thus, lua went underground, practiced in secret by a handful of families—such as the Kaihewalus—for nearly another century. Lua’s resurgence, however, is commonly credited to Charles W. Kenn, a Hawaiian-Japanese-German ‘ōlohe lua and martial artist born in 1907. Kenn learned lua from several teachers, including two who had trained at a royal lua school in the late 1800s. He also studied with renowned sensei Henry Okazaki, who had learned lua from a Hawaiian practitioner after World War I, and incorporated it into his style of jujitsu. Kenn taught lua to five students in Hawai‘i: Richard Paglinawan, Jerry Walker, Mitchell and Dennis Eli, and Moses Kalauokalani. The five would go on to create two lua pā (schools) that continue to carry on the tradition.

Michelle asks me which weapon I’d like, but before I answer she picks up the maka pāhoa, which resembles a giant wooden tuning fork. She weighs it carefully and says beneath her breath, “That’s a badass weapon.”

“OK, come at me like you’re going to choke me,” she orders, and I move toward her with an outstretched hand. She catches my wrist between the wooden prongs and spirals me to the floor in one deft motion. Before I know it, I’m on my elbows with two prongs inches from my eye sockets—hence the weapon’s name, maka pāhoa, or eye dagger. “If this were battle,” Michelle says, “you’d be bludgeoned. Brutal, yeah?”

While women are a growing force in MMA, martial arts in general have mostly been a man’s world. I ask Michelle what that’s been like, navigating through it, having dealt with sexism as she’s fought her way into the halls of fame. “It’s mostly from the toxic keyboard warriors, but they’re exactly why I post a lot of videos showing lua, not just typing about it,” she says. “I want men to see how powerful women can be so they think twice if they come up against a woman in a match or on the street. I also want women to see these videos so they can know how powerful they can be.”

It’s a desire Michelle translated into her popular SHE (Super Hero Experience) workshops over the past few years. With self-defense courses that blend lua techniques with hula movements, Michelle has taught women across the nation to defend themselves when on the ground or thrown up against a wall. She teaches them to handle assaults with crowbars, hammers, zip ties, guns, knives and more. “SHE is my way to empower women to own their space,” she says. “Beyond the self-defense part of it, I teach women how to take control over their choices and opportunities and become whole—mentally, spiritually, emotionally, relationally and financially.”

Has she taught her own daughter or her two grandsons Kaihewalu lua? “The boys are young, still, but yes, she’s learned some. I’d love to see her train more, though. She’s got a wicked straight punch and a front thrust-kick that you’d never see coming!” she laughs, then picks up the ka‘ane, a garrote made of wood and rope and says—for the last time, I hope—“OK, try to hit me!” HH