![]()

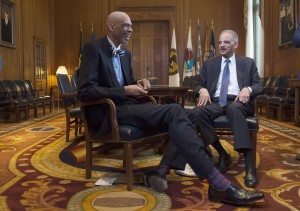

Jan. 29, 2015 | Former Los Angeles Laker Kareem Abdul-Jabbar visits the FBI headquarters to interview Director James Comey for a film about race during a brief visit to D.C. Marvin Joseph/The Washington Post

“You are the man, Mr. Jabbar,” somebody shouts down what is normally a quiet, long hallway in the Department of Justice. Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, who is, in fact, the man, having scored more points than anyone in National Basketball Association history, even Michael, Kobe and LeBron, nods but doesn’t break his stride. He’s on a tight schedule. First, the retired star will interview Attorney General Eric Holder for a documentary he’s making on race. Next, a visit to FBI headquarters, final edits on his column for Time and a hustle to the White House, where Abdul-Jabbar has been asked to stand with President Obama to announce his $215 million precision-medicine initiative. Diagnosed with leukemia in 2008, his cancer has been in remission thanks to target treatments. What else? In the calendar just this winter: Dissing Bill O’Reilly on “Meet the Press.” Promoting his new children’s book. Crooning “We’ll Meet Again” next to country star Toby Keith and inventor Dean Kamen on Stephen Colbert’s lauded send off.

After years of grumbling that he couldn’t get a head coaching gig, Abdul-Jabbar has emerged as much more than an ex-jock diagramming an inbounds pass on a clipboard. He has become a vital, dynamic and unorthodox cultural voice.

“Kareem has something to say, has found a way to say it, and it’s not what you would expect him to say,” says Mike Nizza, the former editor of Esquire Digital who worked with Abdul-Jabbar before he moved his regular columns to Time. “He’s a new kind of public intellectual.”

That morning, as the cameras roll, he and Holder talk fluently about voting rights, hate crimes and the Supreme Court. It’s only when the interview ends that the scene shifts into something more familiar.

Staffers stream into the room, clutching iPhones. They gather, in shifts, for photos around the iconic star. Deborah Morales, Abdul-Jabbar’s manager and the key adviser in promoting his public voice, hands Holder a signed glossy showing the master shooting a patented skyhook over the hated Boston Celtics. By now, elbow room is at a premium.

Abdul-Jabbar on the A train on the way to school in New York. (From the Private Collection of Kareem Abdul-Jabbar)

“He’s the AG’s hero, and he revolutionized the sport,” says Margaret Richardson, Holder’s chief of staff, smiling as she watches the scrum.

A day with Kareem Abdul-Jabbar is nothing like you would expect.

Forget that he’s one of the greatest athletes of all time, a player so dominant that the NCAA banned the dunk for nine years. It’s his mind that moves faster than a Showtime-era fast break.

Abdul-Jabbar is not a name dropper; he’s a fact dropper. References dart across history, pop culture and the special life he’s lived. Mention Boston and he doesn’t reminisce about the Lakers’ epic victory in the 1984-85 finals. He talks of his admiration for the city’s late detective novel master, Robert B. Parker, author of the Spenser series. Ask him about Morales, his unorthodox choice for a manager — she’s white, Jewish and had no idea who he was when they met — and he’ll invoke the name of Gertrude Berg. Gertrude who? You know, the writer and actress who earned an Emmy as the matriarch of the pioneering 1950s sitcom “The Goldbergs.”

Abdul-Jabbar watches lots of TV, loves “True Detective,” “The Wire,” and “Breaking Bad,” and is a lifelong jazz lover who won’t hesitate to hand over his headphones when he thinks you just need to hear Cuban pianist Ernán López Nussa on his iPod.

“You know what they say,” Abdul-Jabbar says with a smile. “Once shared, twice enjoyed.”

And then there are the movies.

Former Los Angeles Laker, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar (left) and the United States Attorney General Eric Holder share a laugh together after Holder joked about Kareem’s bow tie at the Department of Justice in Washington, D.C. on January 29, 2015. (Marvin Joseph/The Washington Post)

[Highlights in the life and career of NBA legend Kareem Abdul-Jabbar on and off the court]

Abdul-Jabbar might be 7-foot-2, notoriously shy and so recognizable he laments that he once got swamped by fans when visiting Mecca. But he is no recluse.

As a kid growing up in Harlem, his mother, Cora, took him to see westerns, particularly anything with William Holden. As an adult, he still prefers a packed theater, a Hebrew National hot dog and a cherry freeze. Oh, and no hiding in back. Abdul-Jabbar likes a seat in the center.

“I want my eye-line to be right in the middle of the screen,” he says. “It’s wonderful. To be in a huge, dark room with strangers. It’s a shared experience.”

All of this would make sense except for one thing. For years, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar was considered one of basketball’s most unpleasant personalities. Moody. Aloof. Taciturn.

“He was a jerk,” says Jackie MacMullan, the veteran sportswriter. “I have sympathy for Kareem because I’ve been around Bill Russell a bit. People always wanting a piece of you. I just always felt Kareem could have managed it better.”

In MacMullan’s 2009 bestseller “When the Game Was Ours,” co-author Magic Johnson recounted watching uncomfortably as Abdul-Jabbar turned away a boy seeking an autograph during a Lakers practice. Johnson smiled and signed.

And MacMullan’s take is echoed by an unexpected source: Abdul-Jabbar.

“It’s true,” he says. “I should have dealt with everyone better.”

It’s a subject Abdul-Jabbar, 67, bared in one his most revelatory pieces for Esquire, “20 Things I Wish I’d Known When I Was 30.”

His top wish: Be more outgoing.

“My shyness and introversion from those days still haunt me,” he wrote. “Fans felt offended, reporters insulted. . . . If I could, I’d tell that nerdy Kareem to suck it up, put down that book you’re using as a shield and, in the immortal words of Capt. Jean-Luc Picard (to prove my nerd cred), ‘Engage!’ ”

If only it were that simple.

“Sometimes there’s that sense that he’s unapproachable,” says NBA Commissioner Adam Silver. “But having been around the world with Kareem, it’s clear he’s incredibly shy and that his shyness gets mistaken for aloofness.”

He is comfortable when a conversation starts naturally, with a police officer walking beside him or a driver taking him to his next appointment. He struggles when a stranger approaches, beaming, to tell him how much he admired his career on the court.

Abdul-Jabbar has been determined to engage more. In the old days, he would decline to sign an autograph, fearing it would lead to a frenzy. Now, he carries a stack of signed basketball cards in his bag, handing them out when a fan approaches.

There are limits. On a bitterly cold day in January, Abdul-Jabbar stood on the sidewalk outside the Department of Justice, filming a stand-up for his race documentary. A man walked straight into the scene, as the camera rolled, to ask for a photo.

“I’m doing something right now,” Abdul-Jabbar said, curtly and with good reason.

In the car a few minutes later, he talks about how he has tried to make peace with celebrity. He remembers meeting former Brooklyn Dodgers slugger Duke Snider at the baseball star’s Hall of Fame induction in 1980.

“What a wonderful guy,” he says. “And that really made me start thinking, ‘Have I been that wonderful guy?’ That’s what changed my attitude. I bled Dodger blue when I was a kid. When they left Brooklyn, I cried. I had heard someone else tell me a story about Carl Furillo. That he was a real a——. I don’t want to be remembered like that. That’s not me. I’ve got that much graciousness in me.”

The writing is not a way to make amends. It’s a passion, dating back to high school, when he worked as a journalist for a community publication in Harlem, and UCLA, where he graduated with a degree in history.

Abdul-Jabbar, who lives in Los Angeles, typically starts in the morning, after breakfast, and writes in cursive on a yellow legal pad. He’s not only open to editing, he embraces it.

“Any writer is actually a rewriter,” says Abdul-Jabbar. “You’ve got to have a structure that’s logical and explains the issue of your story.”

Why does he write? That’s easy.

“You get to be a storyteller,” he says. “And you get to share information in a way that can sometimes change people’s minds and at least make people open up and expand what they know to be true. I think that’s pretty neat.”

He now has almost 1.7 million followers on Twitter. He also has a following among the big names who knew him in his previous incarnation.

“This is not somebody writing a little column,” says Jerry West, the Hall of Famer who served as Lakers coach and general manager. “His language is unparalleled. It doesn’t surprise me. There is no athlete I’ve ever met brighter than Kareem.”

To hear Abdul-Jabbar tell it, he always had ambition. He just needed help. That’s what he found when Morales became his manager a decade ago.

His friends, he admits, do sometimes call her a “yenta,” the Yiddish word for busybody.

When fans approach Abdul-Jabbar, she shoos them off aggressively, sometimes to the point that her client, sitting nearby chomping a slice of cheese pizza, looks down with the mischievous smile of a schoolboy who has gotten a rival in trouble. She also likes to nudge.

At FBI headquarters, Director James Comey gives the star a baseball cap with the agency’s acronym.

“Put it on your head,” Morales nags as photographers ready their cameras. “It’ll look nice.”

Abdul-Jabbar, dapper in a dark suit and white scarf, resists. The cap would spoil that distinguished look.

“Come on,” Morales nudges repeatedly. “Put it on.”

The two met, by chance, in 1994 in Los Angeles International Airport. That led to a friendship. Eleven years later, Abdul-Jabbar replaced his management team.

“No one was stealing from me, but I was dying the death of a thousand cuts,” he says. “I had an accountant and a guy who repped me. All he did was sit around and wait for the phone to ring. Deborah’s proactive. And she has a greater grasp of what I can do and what I should avoid.”

She doesn’t take no for an answer, whether pushing for five more minutes to interview Holder, moving Abdul-Jabbar from Esquire to Time, or raising money for “On the Shoulders of Giants,” an acclaimed 2011 documentary adapted from Abdul-Jabbar’s book about the Harlem Rens, a talented all-black basketball team. Morales also directed the film.

“She can be very hard to get along with,” says Amir Abdul-Jabbar, 34, an orthopedic surgery resident in Louisiana who is one of his five children. (Abdul-Jabbar had three children with his ex-wife, Amir with onetime girlfriend Cheryl Pistono and a fifth with another woman. He now lives alone.) “But I think it may be good for my dad to have someone who is very aggressive and in your face and is very protective of him.”

Morales, for her part, considers Abdul-Jabbar more than a job. He is her mission. She remembers long conversations with the late UCLA coach John Wooden, one of Abdul-Jabbar’s mentors.

“Coach Wooden told me it was my responsibility to make sure Kareem was okay and that he was treated well by mankind,” she says. “He told me how Kareem has been treated because he’s so big and how they approach him and how sensitive he was.”

After his whirlwind D.C. tour, Abdul-Jabbar hops an Amtrak to New York. Late on Friday afternoon, he interviews NBA Commissioner Silver for the race program and meets HBO Sports President Ken Hershman for dinner. The network has commissioned a film about Abdul-Jabbar.

Then it’s back to the yellow pad. Abdul-Jabbar follows a Time column on sexual assault on college campuses to an analysis of Kanye West’s Grammy disruption, arguing against the attack on Beck. “It does a disservice to the very real struggle for racial equality to cry racism at every disappointment.”

That kind of fresh take is part of why Abdul-Jabbar headed off to Sacramento early in February. Mayor Kevin Johnson, the ex-NBA star, had asked him to speak on a panel about race and sports.

“You know what, coaching, I don’t think that was his calling,” says Johnson. “His calling is exactly what he’s doing now. He’s writing a new chapter for America.”

Read More at The Washington Post

[recent_posts type=”post” category=”” count=”3″ offset=”1.” orientation=”horizontal” no_image=”false” fade=”false”]